The outline for this post is as follows:

- The Myth and Its Flaw

- Context and Analysis (divided into multiple sections)

- Posts Providing Further Information and Analysis

- References

This is the "+References" version of this post, which means that this post contains my full list of references and citations. If you would like an abbreviated and easier to read version, then please go to the "main version" of this post.

References are cited as follows: "[#]", with "#" corresponding to the reference number given in the References section at the end of this post.

1. The Myth and Its Flaw

Changing carbon dioxide (CO2) levels correlate with long-term temperature changes on Earth [5; 11 - 21; 447; 1055; 1069, figure 1 (with temperature change in panel d updated in 1057); 1589; 1604; 2576; 2577]. There is also an evidence-based [7 - 10; 34 - 74; 84; 202, chapter 3; 394; 684; 887; 1078; 1101; 1108; 1185; 1357; 1658; 1659; 1741; 1754; 1787; 1831; 1836, pages 22 - 24; 1838, page 57; 2484] scientific consensus [31, table 1 (particularly: 28; 574; 2534; 2535; 2536, updated in 32, figure 2 v007 on page 11, and 33, page 49 {with 2485 - 2495}); 499, page 28 in chapter 2; 500] that humans caused most of the recent global warming, predominately via increasing levels of greenhouse gases such as CO2 (just as there is an evidence-based scientific consensus on other topics [22 - 30; 309 - 312; 314; 331, page 3.8; 399; 943 - 946; 947, table 3 on page 4594; 1363; 1435]). Therefore scientists attribute most of the recent warming to man-made release of CO2. Some critics object to this causal attribution, since the critics claim the attribution involves incorrectly inferring causation from correlation [75 - 83; 85 - 87; 89 - 93; 95; 96]. The critics' claim is the myth this blogpost focuses on.

Proponents of this myth include William Happer [89, page 26; 91], Roy Spencer [76; 89, page 26], S. Fred Singer [85, page 3], Nicola Scafetta [89, page 26], Craig Idso [89, page 26; 96], Robert Carter [90, page 4], Tim Ball [89, page 26], Don Easterbrook [89, page 26], Patrick Moore [93, page 2], Joseph D'Aleo [89, page 26], James Wallace III [89, page 26], Christopher Monckton [78; 81], Willis Eschenbach of the blog WattsUpWithThat [80], Kenneth Richard of the blog NoTricksZone [2476; 2477], the Fraser Institute [77, page 14], Joanne Nova [2142], Warren Meyer [87], CO2 Science [75; 96], Friends of Science [92], Principia Scientific International [79; 86], and other anonymous people whom climate scientists correct [95].

This myth's popularity may help explain why American political conservatives are less likely to accept that human release of greenhouse gases caused most of the recent global warming [28; 301; 573; 575 - 578; 2034] (along with the disproportionate number of conservatives who do not accept that there is solid evidence of global warming [300, figure 2; 573; 1966 - 1968; 2034]).

The myth's flaw: Correlations between CO2 and temperature are not the only line of evidence showing that increased CO2 causes global warming, with CO2 causing most of the recent net warming. Other lines of evidence support this causal attribution, including the same types of evidence that support causal attribution in other scientific fields [99 - 104; 105, section 3.2; 108, section 8.1]. These lines of evidence include (with the corresponding sections in which I discuss each line of evidence):

- section 2.1 : correlation between the cause and its effect

- section 2.2 : plausibility / a well-evidenced causal mechanism illustrating how the cause would produce the effect

- section 2.3 : analogy / comparison to similar causes

- section 2.4 : experimental evidence linking cause and effect

- section 2.5 : strength (cause results in an effect with a large magnitude)

- section 2.6 : a physical gradient (more of the cause results in a greater effect)

- section 2.7 : consistency / reproducibility of the correlation between the cause and the effect

- section 2.8 : primacy / temporality (cause occurs before the effect and is temporally-associated with the effect)

- section 2.9 : specificity (cause results in a specific, predicted, observed set of effects not produced by various other proposed causes)

- section 2.10 : coherence with other lines of evidence / evidence excluding (or incoherent with) other plausible causes

{With the exception of sections 2.1 and 2.4, each section concludes with a summary of the section's overall point. So feel free to use these summaries as a guide through each section.}

One engages in special pleading (or offering an unjustified double-standard) if one accepts these lines of evidence for causation in other fields, while refusing to accept this evidence in the case of CO2 causing warming. Moreover, if myth proponents object to this evidence when it applies to CO2-induced warming, then, if proponents remain consistent in their reasoning, the proponents' logic commits them to objecting to this evidence when it applies to other topics. Thus myth defenders would be committed to objecting to evidence for well-supported causal claims [938; 1556, from 37:54 to 44:55, discussing 1606; 1606 - 1609; 1686; 2136, pages 2 and 8], such as HIV causing AIDS (section 2.3) and smoking causing cancer (sections 2.5 and 2.9). And that would serve as a reductio ad absurdum for the myth proponents' objection. As aptly noted in a 2015 paper discussing other criticisms of the science on human-made climate change:

"Gardiner rightly points out that climate skeptics and deniers are cheating by leveling these concerns at climate science, and not at other sciences (e.g., physics, chemistry, economics, or even evidence-based medicine). Thus, Gardiner insists that if one takes science seriously at all, one must likewise take climate science seriously.

[...]

Nonetheless, there is an important lesson that we ought to draw from Gardiner’s discussion—ceteris paribus, one is not allowed to apply different epistemic standards in one area that one would not apply in another [2136, page 8]."

Changing carbon dioxide (CO2) levels correlate with long-term temperature changes on Earth [5; 11 - 21; 447; 1055; 1069, figure 1 (with temperature change in panel d updated in 1057); 1589; 1604; 2576; 2577]. There is also an evidence-based [7 - 10; 34 - 74; 84; 202, chapter 3; 394; 684; 887; 1078; 1101; 1108; 1185; 1357; 1658; 1659; 1741; 1754; 1787; 1831; 1836, pages 22 - 24; 1838, page 57; 2484] scientific consensus [31, table 1 (particularly: 28; 574; 2534; 2535; 2536, updated in 32, figure 2 v007 on page 11, and 33, page 49 {with 2485 - 2495}); 499, page 28 in chapter 2; 500] that humans caused most of the recent global warming, predominately via increasing levels of greenhouse gases such as CO2 (just as there is an evidence-based scientific consensus on other topics [22 - 30; 309 - 312; 314; 331, page 3.8; 399; 943 - 946; 947, table 3 on page 4594; 1363; 1435]). Therefore scientists attribute most of the recent warming to man-made release of CO2. Some critics object to this causal attribution, since the critics claim the attribution involves incorrectly inferring causation from correlation [75 - 83; 85 - 87; 89 - 93; 95; 96]. The critics' claim is the myth this blogpost focuses on.

Proponents of this myth include William Happer [89, page 26; 91], Roy Spencer [76; 89, page 26], S. Fred Singer [85, page 3], Nicola Scafetta [89, page 26], Craig Idso [89, page 26; 96], Robert Carter [90, page 4], Tim Ball [89, page 26], Don Easterbrook [89, page 26], Patrick Moore [93, page 2], Joseph D'Aleo [89, page 26], James Wallace III [89, page 26], Christopher Monckton [78; 81], Willis Eschenbach of the blog WattsUpWithThat [80], Kenneth Richard of the blog NoTricksZone [2476; 2477], the Fraser Institute [77, page 14], Joanne Nova [2142], Warren Meyer [87], CO2 Science [75; 96], Friends of Science [92], Principia Scientific International [79; 86], and other anonymous people whom climate scientists correct [95].

This myth's popularity may help explain why American political conservatives are less likely to accept that human release of greenhouse gases caused most of the recent global warming [28; 301; 573; 575 - 578; 2034] (along with the disproportionate number of conservatives who do not accept that there is solid evidence of global warming [300, figure 2; 573; 1966 - 1968; 2034]).

This myth's popularity may help explain why American political conservatives are less likely to accept that human release of greenhouse gases caused most of the recent global warming [28; 301; 573; 575 - 578; 2034] (along with the disproportionate number of conservatives who do not accept that there is solid evidence of global warming [300, figure 2; 573; 1966 - 1968; 2034]).

The myth's flaw: Correlations between CO2 and temperature are not the only line of evidence showing that increased CO2 causes global warming, with CO2 causing most of the recent net warming. Other lines of evidence support this causal attribution, including the same types of evidence that support causal attribution in other scientific fields [99 - 104; 105, section 3.2; 108, section 8.1]. These lines of evidence include (with the corresponding sections in which I discuss each line of evidence):

- section 2.1 : correlation between the cause and its effect

- section 2.2 : plausibility / a well-evidenced causal mechanism illustrating how the cause would produce the effect

- section 2.3 : analogy / comparison to similar causes

- section 2.4 : experimental evidence linking cause and effect

- section 2.5 : strength (cause results in an effect with a large magnitude)

- section 2.6 : a physical gradient (more of the cause results in a greater effect)

- section 2.7 : consistency / reproducibility of the correlation between the cause and the effect

- section 2.8 : primacy / temporality (cause occurs before the effect and is temporally-associated with the effect)

- section 2.9 : specificity (cause results in a specific, predicted, observed set of effects not produced by various other proposed causes)

- section 2.10 : coherence with other lines of evidence / evidence excluding (or incoherent with) other plausible causes

{With the exception of sections 2.1 and 2.4, each section concludes with a summary of the section's overall point. So feel free to use these summaries as a guide through each section.}

One engages in special pleading (or offering an unjustified double-standard) if one accepts these lines of evidence for causation in other fields, while refusing to accept this evidence in the case of CO2 causing warming. Moreover, if myth proponents object to this evidence when it applies to CO2-induced warming, then, if proponents remain consistent in their reasoning, the proponents' logic commits them to objecting to this evidence when it applies to other topics. Thus myth defenders would be committed to objecting to evidence for well-supported causal claims [938; 1556, from 37:54 to 44:55, discussing 1606; 1606 - 1609; 1686; 2136, pages 2 and 8], such as HIV causing AIDS (section 2.3) and smoking causing cancer (sections 2.5 and 2.9). And that would serve as a reductio ad absurdum for the myth proponents' objection. As aptly noted in a 2015 paper discussing other criticisms of the science on human-made climate change:

"Gardiner rightly points out that climate skeptics and deniers are cheating by leveling these concerns at climate science, and not at other sciences (e.g., physics, chemistry, economics, or even evidence-based medicine). Thus, Gardiner insists that if one takes science seriously at all, one must likewise take climate science seriously.

[...]

Nonetheless, there is an important lesson that we ought to draw from Gardiner’s discussion—ceteris paribus, one is not allowed to apply different epistemic standards in one area that one would not apply in another [2136, page 8]."

"Gardiner rightly points out that climate skeptics and deniers are cheating by leveling these concerns at climate science, and not at other sciences (e.g., physics, chemistry, economics, or even evidence-based medicine). Thus, Gardiner insists that if one takes science seriously at all, one must likewise take climate science seriously.

[...]

Nonetheless, there is an important lesson that we ought to draw from Gardiner’s discussion—ceteris paribus, one is not allowed to apply different epistemic standards in one area that one would not apply in another [2136, page 8]."

2. Context and Analysis

Section 2.1: Overview + correlation

Evidence can reveal correlations/associations, as with the correlation between saturated fat intake vs. heart disease [853 - 859; 860, chapter 1; 1268] (though a number of commentators object to this association [840 - 850], while other commentators point out flaws in these objections [850 - 853], in line with evidence that vegetarian diets that limit saturated fat intake [1092; 1483] also improve heart-disease-related metrics [1090; 1091; 1482 - 1484]). In addition to correlation, scientists also investigate cause and effect. To aid in this pursuit, scientists and philosophers of science developed a number of frameworks for attributing an effect to a specific cause or causes. These frameworks for causal attribution include Bradford Hill considerations [99 - 104; 105, section 3.2; 108, section 8.1], Granger causality [8 - 10; 108, section 8.2; 1873 (with 2386); 2042; reviewed in: 2387; 2484], John Stuart Mill's methods for causal inference [107; 108, section 5.2], David Hume's methods (Hume also defended skepticism regarding causation in general) [106; 107; 108, section 5.1], and concepts from information theory [7; 2478], among others [108 - 111; 2478].

One can apply these aforementioned frameworks to causation in different scientific fields, as has been done [72; 2059; 2143; 2478] for information theory [7; 2478] and Granger causality [8 - 10; 2478; 2484] with respect to increased CO2 causing warming. But what justifies the claim that increased CO2 causes warming? Is a correlation between CO2 changes and temperature changes enough to justify this causal claim? To make these questions more vivid, suppose someone presented the following graphs showing a correlation between changing CO2 levels and temperature changes:

Figure 1: (Top panel) Global CO2 levels and global surface temperature change from 1910 - 2017. CO2 levels are shown in parts per million per volume (ppmv), which is equivalent to ppm. The temperature is relative to a baseline of 1951 - 1980, from NASA's Goddard Institute for Space Studies Surface Temperature analysis version 4 (GISS/GISSTEMP) [2090, figure 1]. A number of other sources [72, figure 1; 1754, figure 1; 2052, figure 1; 2059, figure 2a; 2098, figure 2; 2099, figure 4; 2100, pages 6 and 7; 2101 - 2103; 2107; 2134; 2138; 2144; 2185, figure 1], including published studies [72, figure 1; 1754, figure 1; 2052, figure 1; 2059, figure 2a; 2185, figure 1], offer similar depictions of CO2 levels in relation to global temperature changes.

This figure may overestimate 1940s - 1970s cooling due to uncertainties tied to changes in temperature monitoring practices during World War II [762, figure 4; 1659; 1677; 1688; 1731; 1920; 1947; 2175; 2176, with 1807, figure 3b; 2252], as I discuss in "Myth: Karl et al. of the NOAA Misleadingly Altered Ocean Temperature Records to Increase Global Warming". Figure 23 below addresses this issue.

This top panel is not the best way to present a correlation that supports the theory of CO2-induced warming. For instance, there is a logarithmic, non-linear relationship between increased CO2 and increased temperature [72; 151; 349, pages 736 and 740; 918, chapter 4; 1074]. The middle panel better accounts for this logarithmic relationship. So a 30ppm increase in CO2 would have a greater warming effect during the lower CO2 levels of the early 20th century vs. during the greater CO2 levels of the late 20th century. The logarithmic relationship between increased CO2 and CO2-induced warming [72; 151; 349, pages 736 and 740; 918, chapter 4; 1074] means that a near-exponential increase in CO2 [20; 121, page 3; 482; 493, figure 1; 590, figure 2; 923; 1062, figure 6; 1400, figures 6, 7, 8, and 9; 1830; 2568] resulted in a more-linear rate of CO2-induced warming [72; 485 - 491; 1413, figure 4; 1415] across the 20th century [35, page 2349; 72; 487; 492; 493; 494, page 1; 1413, figure 4; 1415]. The aforementioned more-linear CO2-induced warming combined with temperature trends caused by other factors, such as aerosols, yielding the observed 20th century temperature trend. Thus increased greenhouse gases contributed between a quarter to a half of the 1910s - 1940s warming [1078, figure 3 on page 7; 1360; 1361]. Other factors, such as increased solar output, contributed to 1910s - 1940s warming [1078, figure 3, on page 7; 1360; 1361; 1659]. But these factors can be ruled out as primary causes of post-1960s warming. The evidence ruling out these causes also rules in increased CO2 as the primary cause of post-1960s warming (see sections 2.5, 2.6, 2.9, and 2.10 for more on this, along with figures 22, 23, and 25).

(Middle panel) Relative global surface temperature change and the logarithm of CO2 concentration from 1880 - 2018. Relative temperature comes from NASA's Goddard Institute for Space Studies Surface Temperature analysis (GISS/GISSTEMP). Each 4-digit number represents a year, with a corresponding CO2 level on the x-axis and a relative temperature on the y-axis. For example, 2018 was ~0.8°C above the baseline average temperature, with a corresponding CO2 concentration of ~408 parts per million (ppm) [2138]. Though not depicted in this figure, 2019 was ~0.9°C above the baseline average temperature, falling slightly below 2016 as the second-warmest year in GISS/GISSTEMP and other surface temperature trend analyses [1776; 2060; 2066; 2067; 2068 - 2071, generated using 741, as per 742; 2184]. 2019's corresponding CO2 level was ~411ppm [117; 1408; 1409; 1432; 1620; 1837; 2096]. The "r" on the top left states the correlation coefficient [2138]; this value is close to 1, indicating a strong, positive correlation between relative temperature and the natural logarithm of CO2 concentration. The logarithm of CO2 concentration is used here since there is a logarithmic relationship between increased CO2 and increased temperature [72; 151; 349, pages 736 and 740; 918, chapter 4; 1074]. Other peer-reviewed [72, figure 1; 1754, figure 1] and non-peer-reviewed sources offer a similar analysis [ex: 2145; 2147]. The trend-line for this graph implies ~2.4°C of warming per doubling of CO2, assuming the long-term net warming trend is equal to CO2-induced warming trend (y = 8.07{log(CO2) - 20.22}) [2138; 2376]. CO2 here is used a surrogate for not only CO2 but other anthropogenic factors such as increases in methane (CH4), under the assumption that a doubling of CO2 implies a similar doubling of these factors [72; 2585]. The slope likely under-estimates the equilibrium climate sensitivity discussed in section 2.5, since this slope does not account for factors in that section, such as the thermal inertia of the deep oceans [1221; 1392 - 1396; 1594, page 585; 1664; 1767, Results section; 2377; 2378]. This implies that the surface warming lags the CO2 increase, as the deep oceans take up most of the energy first [434, page 26; 1221; 1392 - 1396; 1614, pages 1104 and 1106; 1664; 1767, Results section; 2377; 2378; 2409, page 2; 2566, page 962].

At least 7 other thermometer-based (a.k.a. instrumental) [1013, figure 1b; 1078, figure 1A; 1659, page 4895 (with 1688 and 2162); 1739, figure 1; 2044, figure 8 [with: 2575]; 2066; 2067; 2148, figure 13; 2149; 2246] analyses and 1 climate-contrarian-endorsed [2359, citing 2360; 2363] re-analysis [2357, generated using 741, as per 742 (from 2358)] confirm the post-1900 GISS/GISSTEMP temperature trend shown in the top and middle panels, as per figures 21 and 22. This includes the fossil-fuel-industry-funded [2217 - 2219] and climate-contrarian-endorsed [2220 - 2222] Berkeley Earth analysis [1013, figure 1b; 1659, figure 5; 1739, figure 1; 2044, figure 8 [with: 2575]; 2066; 2148, figure 13]. However, GISS/GISSTEMP may still over-estimate 1940s - 1970s cooling [762, figure 4; 1659; 1677; 1688; 1731; 1920; 1947; 2175; 2176, with 1807, figure 3b; 2252], as discussed above with respect to the top panel and illustrated below in figure 23. Scientists will likely introduce more instrumental surface analyses in the future; this includes the upcoming GloSAT analysis, which is intended to cover global surface air trends dating back to the late 1700s [2159 - 2164]. And at least 3 re-analyses that incorporate data from diverse sources, cover the post-1979 time-period and confirm the overall GISS/GISSTEMP trend for that period [2066; 2067; 2149; 2229 - 2231, generated using 741, as per 742; 2246]. This includes the climate-contrarian-endorsed [2223 - 2228; 2443] ERA5 [2066; 2067; 2149; 2229, generated using 741, as per 742] and JRA-55 [2067; 2231, generated using 741, as per 742] re-analyses. I discuss the merits of various re-analyses and instrumental analyses in section 2.1 of "Myth: The IPCC's 1990 Report Over-estimated Greenhouse-gas-induced Global Warming".

Scientists tested and validated the data adjustment procedures used in instrumental temperature trend analyses [ex: 752; 1451, page 9840; 1932 - 1934; 1938; 1939; 2208 - 2211; 2406]. Non-experts examining the raw data further replicated the warming trend from mainstream instrumental analyses [2150 - 2156; 2157, sections 6.3 and 6.4 on pages 45 - 49; 2186; 2213]; multiproxy analyses also confirm the instrumental warming trend [492; 761 - 763; 1172; 1173; 1807; 1831, figure 1c; 2176], as do other indirect measures that do not use thermometer data for air temperatures [760; 1173, figure 4; 1503, using 741, as per 742, with the re-analyses from 760 and 1504; 1807, figure 3]. Moreover, other signs of industrial-era surface warming occurred, such as rapid ice melt and sea level rise [762; 1433, figure 3 on page 8, citing 467 (with 2374, figures 9 and 10A); 1434, figure 3a on page 511; 1522; 1524]. And satellite-based analyses confirm recent surface warming trends [547; 754; 1689; 1813; 2158; 2169, using 1689; 2232, using 1689; 2396, with 1776 (and 2397, generated using 741, as per 742)]; recent global warming occurred not only in surface temperatures records, but was also reflected in deep ocean warming (see figure 24), bulk atmospheric (tropospheric) trends from satellite-based analyses and weather balloons, sea level rise acceleration, etc., as shown in "Myth: No Global Warming for Two Decades". Thus there exist consilient/convergent, reproducible lines of evidence supporting the stated warming trend. Such consilience further increases the likelihood that the observed warming trend is real [24; 547; 550, pages 14, 42, 120, and 122; 555; 1855; 2233, from 6:10 to 7:36; 2537]. Despite all this evidence, a myth proponent might still object to the CO2-temperature correlation by offering a baseless conspiracy theory in which NASA faked the GISS/GISSTEMP analysis, along with faking all these other signs of warming. I respond to this paranoid delusion in section 2.2 of "Myth: The IPCC's 2007 ~0.2°C/decade Model-based Projection Failed and Judith Curry's Forecast was More Reliable" and in response to objection 1 in section 3.1 of "John Christy, Climate Models, and Long-term Tropospheric Warming".

(Bottom panel) CO2 level and temperature change estimated from an Antarctic ice core [12]; a 2019 study explained similar results over a longer time-period using climate models [1589; 1590]. 1°C of Antarctic warming from this figure translates to ~0.6°C of global warming [118 (to be read with 1655 - 1657; 1861); 1589; 1604, figure 12]. The figures's data is taken from two published studies [112; 113]. "Years before present" (BP) on the x-axis means "years before 1950" [114]; this point sometimes confuses contrarians [982, from 5:33 to 7:52; 1033, from 8:13 to 9:10; 1035, page 95; 1039]. And the aforementioned data stops by about 38 BP [115; 116], which is equivalent to ~1912. So this figure does not include most of the warming and CO2 increase since the 20th century; CO2 levels are now above 410ppm [117; 1406; 1408; 1409; 1432; 1620; 1837; 2096; 2568], the highest they have been in at least 2 million years [202, pages 11, 31, 53, 133, and 151; 1589; 1662; 1922; 2085; 2086; 2133].

Along with temperature, sea level also increased with increasing CO2 and decreased with decreasing CO2 in the distant past [14; 469; 1069; 1604, figure 12; 1639], as per warming-induced sea level rise from melting land ice and thermal expansion of ocean water [466 - 468; 1069; 1070; 1721]. Moreover, warming-induced, man-made sea level rise also occurred during the industrial era [470; 472 - 480]. A number of other sources [3 - 6; 18 (to be read with 2104 - 2106; 2346; 2347; 2392, from 14:52 to 16:30; 2398 - 2400); 118 (to be read with 1655 - 1657; 1861); 187; 363; 448, with 449; 640, page 1730; 642, page 435; 949, pages 44 and 45; 1069; 1604; 1861; 1862; 1869] discuss how changes in greenhouse gas levels impact the ice age glacial-interglacial cycles shown in this bottom panel; see section 2.8 for further discussion.

(In section 2.8, I rebut the argument that since figure 1's bottom panel shows that CO2 increases lag temperature increases, figure 1 undermines the case for CO2-induced warming. And in "Myth: An Ice Core Shows a Spike in CO2 Levels without a Spike in Temperature", I debunk attempts to use a modified version of figure 1 to argue that CO2 does not cause warming.)

Section 2.1: Overview + correlation

Evidence can reveal correlations/associations, as with the correlation between saturated fat intake vs. heart disease [853 - 859; 860, chapter 1; 1268] (though a number of commentators object to this association [840 - 850], while other commentators point out flaws in these objections [850 - 853], in line with evidence that vegetarian diets that limit saturated fat intake [1092; 1483] also improve heart-disease-related metrics [1090; 1091; 1482 - 1484]). In addition to correlation, scientists also investigate cause and effect. To aid in this pursuit, scientists and philosophers of science developed a number of frameworks for attributing an effect to a specific cause or causes. These frameworks for causal attribution include Bradford Hill considerations [99 - 104; 105, section 3.2; 108, section 8.1], Granger causality [8 - 10; 108, section 8.2; 1873 (with 2386); 2042; reviewed in: 2387; 2484], John Stuart Mill's methods for causal inference [107; 108, section 5.2], David Hume's methods (Hume also defended skepticism regarding causation in general) [106; 107; 108, section 5.1], and concepts from information theory [7; 2478], among others [108 - 111; 2478].

One can apply these aforementioned frameworks to causation in different scientific fields, as has been done [72; 2059; 2143; 2478] for information theory [7; 2478] and Granger causality [8 - 10; 2478; 2484] with respect to increased CO2 causing warming. But what justifies the claim that increased CO2 causes warming? Is a correlation between CO2 changes and temperature changes enough to justify this causal claim? To make these questions more vivid, suppose someone presented the following graphs showing a correlation between changing CO2 levels and temperature changes:

(In section 2.8, I rebut the argument that since figure 1's bottom panel shows that CO2 increases lag temperature increases, figure 1 undermines the case for CO2-induced warming. And in "Myth: An Ice Core Shows a Spike in CO2 Levels without a Spike in Temperature", I debunk attempts to use a modified version of figure 1 to argue that CO2 does not cause warming.)

One can apply these aforementioned frameworks to causation in different scientific fields, as has been done [72; 2059; 2143; 2478] for information theory [7; 2478] and Granger causality [8 - 10; 2478; 2484] with respect to increased CO2 causing warming. But what justifies the claim that increased CO2 causes warming? Is a correlation between CO2 changes and temperature changes enough to justify this causal claim? To make these questions more vivid, suppose someone presented the following graphs showing a correlation between changing CO2 levels and temperature changes:

|

Figure 1: (Top panel) Global CO2 levels and global surface temperature change from 1910 - 2017. CO2 levels are shown in parts per million per volume (ppmv), which is equivalent to ppm. The temperature is relative to a baseline of 1951 - 1980, from NASA's Goddard Institute for Space Studies Surface Temperature analysis version 4 (GISS/GISSTEMP) [2090, figure 1]. A number of other sources [72, figure 1; 1754, figure 1; 2052, figure 1; 2059, figure 2a; 2098, figure 2; 2099, figure 4; 2100, pages 6 and 7; 2101 - 2103; 2107; 2134; 2138; 2144; 2185, figure 1], including published studies [72, figure 1; 1754, figure 1; 2052, figure 1; 2059, figure 2a; 2185, figure 1], offer similar depictions of CO2 levels in relation to global temperature changes. This figure may overestimate 1940s - 1970s cooling due to uncertainties tied to changes in temperature monitoring practices during World War II [762, figure 4; 1659; 1677; 1688; 1731; 1920; 1947; 2175; 2176, with 1807, figure 3b; 2252], as I discuss in "Myth: Karl et al. of the NOAA Misleadingly Altered Ocean Temperature Records to Increase Global Warming". Figure 23 below addresses this issue. This top panel is not the best way to present a correlation that supports the theory of CO2-induced warming. For instance, there is a logarithmic, non-linear relationship between increased CO2 and increased temperature [72; 151; 349, pages 736 and 740; 918, chapter 4; 1074]. The middle panel better accounts for this logarithmic relationship. So a 30ppm increase in CO2 would have a greater warming effect during the lower CO2 levels of the early 20th century vs. during the greater CO2 levels of the late 20th century. The logarithmic relationship between increased CO2 and CO2-induced warming [72; 151; 349, pages 736 and 740; 918, chapter 4; 1074] means that a near-exponential increase in CO2 [20; 121, page 3; 482; 493, figure 1; 590, figure 2; 923; 1062, figure 6; 1400, figures 6, 7, 8, and 9; 1830; 2568] resulted in a more-linear rate of CO2-induced warming [72; 485 - 491; 1413, figure 4; 1415] across the 20th century [35, page 2349; 72; 487; 492; 493; 494, page 1; 1413, figure 4; 1415]. The aforementioned more-linear CO2-induced warming combined with temperature trends caused by other factors, such as aerosols, yielding the observed 20th century temperature trend. Thus increased greenhouse gases contributed between a quarter to a half of the 1910s - 1940s warming [1078, figure 3 on page 7; 1360; 1361]. Other factors, such as increased solar output, contributed to 1910s - 1940s warming [1078, figure 3, on page 7; 1360; 1361; 1659]. But these factors can be ruled out as primary causes of post-1960s warming. The evidence ruling out these causes also rules in increased CO2 as the primary cause of post-1960s warming (see sections 2.5, 2.6, 2.9, and 2.10 for more on this, along with figures 22, 23, and 25). (Middle panel) Relative global surface temperature change and the logarithm of CO2 concentration from 1880 - 2018. Relative temperature comes from NASA's Goddard Institute for Space Studies Surface Temperature analysis (GISS/GISSTEMP). Each 4-digit number represents a year, with a corresponding CO2 level on the x-axis and a relative temperature on the y-axis. For example, 2018 was ~0.8°C above the baseline average temperature, with a corresponding CO2 concentration of ~408 parts per million (ppm) [2138]. Though not depicted in this figure, 2019 was ~0.9°C above the baseline average temperature, falling slightly below 2016 as the second-warmest year in GISS/GISSTEMP and other surface temperature trend analyses [1776; 2060; 2066; 2067; 2068 - 2071, generated using 741, as per 742; 2184]. 2019's corresponding CO2 level was ~411ppm [117; 1408; 1409; 1432; 1620; 1837; 2096]. The "r" on the top left states the correlation coefficient [2138]; this value is close to 1, indicating a strong, positive correlation between relative temperature and the natural logarithm of CO2 concentration. The logarithm of CO2 concentration is used here since there is a logarithmic relationship between increased CO2 and increased temperature [72; 151; 349, pages 736 and 740; 918, chapter 4; 1074]. Other peer-reviewed [72, figure 1; 1754, figure 1] and non-peer-reviewed sources offer a similar analysis [ex: 2145; 2147]. The trend-line for this graph implies ~2.4°C of warming per doubling of CO2, assuming the long-term net warming trend is equal to CO2-induced warming trend (y = 8.07{log(CO2) - 20.22}) [2138; 2376]. CO2 here is used a surrogate for not only CO2 but other anthropogenic factors such as increases in methane (CH4), under the assumption that a doubling of CO2 implies a similar doubling of these factors [72; 2585]. The slope likely under-estimates the equilibrium climate sensitivity discussed in section 2.5, since this slope does not account for factors in that section, such as the thermal inertia of the deep oceans [1221; 1392 - 1396; 1594, page 585; 1664; 1767, Results section; 2377; 2378]. This implies that the surface warming lags the CO2 increase, as the deep oceans take up most of the energy first [434, page 26; 1221; 1392 - 1396; 1614, pages 1104 and 1106; 1664; 1767, Results section; 2377; 2378; 2409, page 2; 2566, page 962]. At least 7 other thermometer-based (a.k.a. instrumental) [1013, figure 1b; 1078, figure 1A; 1659, page 4895 (with 1688 and 2162); 1739, figure 1; 2044, figure 8 [with: 2575]; 2066; 2067; 2148, figure 13; 2149; 2246] analyses and 1 climate-contrarian-endorsed [2359, citing 2360; 2363] re-analysis [2357, generated using 741, as per 742 (from 2358)] confirm the post-1900 GISS/GISSTEMP temperature trend shown in the top and middle panels, as per figures 21 and 22. This includes the fossil-fuel-industry-funded [2217 - 2219] and climate-contrarian-endorsed [2220 - 2222] Berkeley Earth analysis [1013, figure 1b; 1659, figure 5; 1739, figure 1; 2044, figure 8 [with: 2575]; 2066; 2148, figure 13]. However, GISS/GISSTEMP may still over-estimate 1940s - 1970s cooling [762, figure 4; 1659; 1677; 1688; 1731; 1920; 1947; 2175; 2176, with 1807, figure 3b; 2252], as discussed above with respect to the top panel and illustrated below in figure 23. Scientists will likely introduce more instrumental surface analyses in the future; this includes the upcoming GloSAT analysis, which is intended to cover global surface air trends dating back to the late 1700s [2159 - 2164]. And at least 3 re-analyses that incorporate data from diverse sources, cover the post-1979 time-period and confirm the overall GISS/GISSTEMP trend for that period [2066; 2067; 2149; 2229 - 2231, generated using 741, as per 742; 2246]. This includes the climate-contrarian-endorsed [2223 - 2228; 2443] ERA5 [2066; 2067; 2149; 2229, generated using 741, as per 742] and JRA-55 [2067; 2231, generated using 741, as per 742] re-analyses. I discuss the merits of various re-analyses and instrumental analyses in section 2.1 of "Myth: The IPCC's 1990 Report Over-estimated Greenhouse-gas-induced Global Warming". Scientists tested and validated the data adjustment procedures used in instrumental temperature trend analyses [ex: 752; 1451, page 9840; 1932 - 1934; 1938; 1939; 2208 - 2211; 2406]. Non-experts examining the raw data further replicated the warming trend from mainstream instrumental analyses [2150 - 2156; 2157, sections 6.3 and 6.4 on pages 45 - 49; 2186; 2213]; multiproxy analyses also confirm the instrumental warming trend [492; 761 - 763; 1172; 1173; 1807; 1831, figure 1c; 2176], as do other indirect measures that do not use thermometer data for air temperatures [760; 1173, figure 4; 1503, using 741, as per 742, with the re-analyses from 760 and 1504; 1807, figure 3]. Moreover, other signs of industrial-era surface warming occurred, such as rapid ice melt and sea level rise [762; 1433, figure 3 on page 8, citing 467 (with 2374, figures 9 and 10A); 1434, figure 3a on page 511; 1522; 1524]. And satellite-based analyses confirm recent surface warming trends [547; 754; 1689; 1813; 2158; 2169, using 1689; 2232, using 1689; 2396, with 1776 (and 2397, generated using 741, as per 742)]; recent global warming occurred not only in surface temperatures records, but was also reflected in deep ocean warming (see figure 24), bulk atmospheric (tropospheric) trends from satellite-based analyses and weather balloons, sea level rise acceleration, etc., as shown in "Myth: No Global Warming for Two Decades". Thus there exist consilient/convergent, reproducible lines of evidence supporting the stated warming trend. Such consilience further increases the likelihood that the observed warming trend is real [24; 547; 550, pages 14, 42, 120, and 122; 555; 1855; 2233, from 6:10 to 7:36; 2537]. Despite all this evidence, a myth proponent might still object to the CO2-temperature correlation by offering a baseless conspiracy theory in which NASA faked the GISS/GISSTEMP analysis, along with faking all these other signs of warming. I respond to this paranoid delusion in section 2.2 of "Myth: The IPCC's 2007 ~0.2°C/decade Model-based Projection Failed and Judith Curry's Forecast was More Reliable" and in response to objection 1 in section 3.1 of "John Christy, Climate Models, and Long-term Tropospheric Warming". (Bottom panel) CO2 level and temperature change estimated from an Antarctic ice core [12]; a 2019 study explained similar results over a longer time-period using climate models [1589; 1590]. 1°C of Antarctic warming from this figure translates to ~0.6°C of global warming [118 (to be read with 1655 - 1657; 1861); 1589; 1604, figure 12]. The figures's data is taken from two published studies [112; 113]. "Years before present" (BP) on the x-axis means "years before 1950" [114]; this point sometimes confuses contrarians [982, from 5:33 to 7:52; 1033, from 8:13 to 9:10; 1035, page 95; 1039]. And the aforementioned data stops by about 38 BP [115; 116], which is equivalent to ~1912. So this figure does not include most of the warming and CO2 increase since the 20th century; CO2 levels are now above 410ppm [117; 1406; 1408; 1409; 1432; 1620; 1837; 2096; 2568], the highest they have been in at least 2 million years [202, pages 11, 31, 53, 133, and 151; 1589; 1662; 1922; 2085; 2086; 2133]. Along with temperature, sea level also increased with increasing CO2 and decreased with decreasing CO2 in the distant past [14; 469; 1069; 1604, figure 12; 1639], as per warming-induced sea level rise from melting land ice and thermal expansion of ocean water [466 - 468; 1069; 1070; 1721]. Moreover, warming-induced, man-made sea level rise also occurred during the industrial era [470; 472 - 480]. A number of other sources [3 - 6; 18 (to be read with 2104 - 2106; 2346; 2347; 2392, from 14:52 to 16:30; 2398 - 2400); 118 (to be read with 1655 - 1657; 1861); 187; 363; 448, with 449; 640, page 1730; 642, page 435; 949, pages 44 and 45; 1069; 1604; 1861; 1862; 1869] discuss how changes in greenhouse gas levels impact the ice age glacial-interglacial cycles shown in this bottom panel; see section 2.8 for further discussion. |

(In section 2.8, I rebut the argument that since figure 1's bottom panel shows that CO2 increases lag temperature increases, figure 1 undermines the case for CO2-induced warming. And in "Myth: An Ice Core Shows a Spike in CO2 Levels without a Spike in Temperature", I debunk attempts to use a modified version of figure 1 to argue that CO2 does not cause warming.)

The CO2-temperature correlation is fairly strong [72, figure 1; 1754, figure 1; 2052, figure 1; 2059, figure 2a; 2090, figure 1; 2138; 2141; 2185, figure 1], with a correlation coefficient of ~0.9 [72, table 1; 2138; 2141]; the strong correlation is apparent enough that even non-experts can show it [ex: 2145; 2147; 2198; 2199; 2376]. Other sources also show a long-term correlation between CO2 and temperature changes [5; 11; 13 - 21; 447; 1055; 1069, figure 1, with temperature change in panel d updated in 1057; 1589; 1604; 1639; 2141; 2576; 2577]. For instance, in section 2.10 I present other CO2-induced temperature trend correlations during the distant past and during the recent industrial-era. One common reply to this correlation is to claim that "correlation does not imply causation," as in the case of spurious correlations [1790 - 1796; 1805; 1806] between stork population and human birth rates [1805; 1806], or between a country's chocolate consumption and their number of Nobel laureates [1793 - 1795]. So claiming that CO2 causes warming involves incorrectly inferring causation from correlation [75 - 83; 85 - 87; 89 - 93; 95; 96]; this is the myth this blogpost focuses on.

Though it is true that correlation does not guarantee causation, correlation/association should be used as part of a cumulative case for causation. In this blogpost I illustrate this point by applying some methods of causal inference to show that CO2 caused global warming. I will primarily focus on Bradford Hill considerations used for inferring causation [99 - 104; 105, section 3.2; 108, section 8.1]. I will also follow Bradford Hill's example [99] and explain how these considerations apply not only to the CO2-temperature causal relationship, but also to causal relationships in numerous other branches of science. This should provide broader context on how scientists support causal claims using these considerations.

So if myth defenders object to these considerations, then they are not simply objecting to climate science; they are also objecting to causal attribution, and trend-based reasoning, in other scientific fields [938; 1556, from 37:54 to 44:55, discussing 1606; 1606 - 1609; 1686; 2136, page 2]. As the climate scientist Gavin Schmidt [95; 1121; 1355; 1605], and other scientists [6; 1119; 1120; 1356; 1358], have noted:

So if myth defenders object to these considerations, then they are not simply objecting to climate science; they are also objecting to causal attribution, and trend-based reasoning, in other scientific fields [938; 1556, from 37:54 to 44:55, discussing 1606; 1606 - 1609; 1686; 2136, page 2]. As the climate scientist Gavin Schmidt [95; 1121; 1355; 1605], and other scientists [6; 1119; 1120; 1356; 1358], have noted:

"Note that it helps enormously to think about attribution in contexts that don’t have anything to do with anthropogenic [a.k.a. human-made] causes. For some reason that allows people to think a little bit more clearly about the problem [95]."

(A note on analogies: Throughout this blogpost, I make analogies between CO2-induced warming and other topics, such saturated-fat-induced heart disease and HIV causing AIDS. The basic structure of these analogical arguments [1608; 1609; 2125 - 2130] is:

My use of Bradford Hill considerations should debunk the myth that correlations between CO2 and temperature changes are the only line of evidence showing that CO2 causes warming. These considerations will also support the evidence-based [7 - 10; 34 - 74; 84; 202, chapter 3; 394; 684; 887; 1078; 1101; 1108; 1185; 1357; 1658; 1659; 1741; 1754; 1787; 1831; 1836, pages 22 - 24; 1838, page 57; 2484] scientific consensus [31, table 1 (particularly: 28; 574; 2534; 2535; 2536, updated in 32, figure 2 v007 on page 11, and 33, page 49 {with 2485 - 2495}); 499, page 28 in chapter 2; 500] that humans caused most of the post-1950s and post-1970s net global warming, primarily through humanity's release of CO2. This point extends to the industrial-era [35, page 2349; 72; 487; 492; 493; 494, page 1; 762; 1831; 2166] global warming of the late 19th, 20th, and early 21st centuries [35; 37; 45; 57; 60; 61; 63 - 65; 68; 69; 72; 74; 394; 887; 1078, figure 1A; 1150, figure 8.18 on page 699; 1357; 1659, with 1688; 1754; 1831], as per figures 22, 23, and 25. For instance, the Intergovernmental Panel of Climate Change (IPCC) notes that there is a 95% or greater [119, page 3] chance that most of the global warming from 1951 to 2010 was caused by humans [121, page 4; 373, page 869 and 884]. The IPCC also notes that there is 90% or greater chance [119, page 3] that man-made increases in greenhouses gases caused most of the warming from 1951 to 2010 [373, pages 869 and 884], with CO2 being the primary greenhouse gas released by human activity [121, figure SPM.2 on page 5]..

So let's see how Bradford Hill considerations support this evidence-based consensus on CO2-induced warming, starting with the metric of "plausibility."

- compare two or more matters

- point out a relevant similarity or difference between those matters

- draw a conclusion from that similarity or difference

Logical reasoning works in this way. For instance, one can point out that two arguments are both instances of modus ponens, and from that draw the conclusion that both arguments are formerly valid, such that if their premises are true, then their conclusion is true. Or one can point out that two arguments use wishful thinking, making both arguments not cogent. I use analogies for a number of reasons, such as exposing the special pleading involved in myth proponents defending the myth using ridiculous arguments they would not accept in another scientific topics [938; 1556, from 37:54 to 44:55, discussing 1606; 1606 - 1609; 1686; 2136, page 2]. The analogies also provide a reductio ad absurdum by showing that if the myth advocate's reasoning was applied to other scientific topics, then it would commit them to not accepting well-supported causal claims that they actually should accept. And research shows that analogies to other topics can effectively expose errors in one's scientific reasoning [938; 1556, from 37:54 to 44:55, discussing 1606; 1606 - 1609; 1686; 2127 - 2130; 2272; 2384].)

My use of Bradford Hill considerations should debunk the myth that correlations between CO2 and temperature changes are the only line of evidence showing that CO2 causes warming. These considerations will also support the evidence-based [7 - 10; 34 - 74; 84; 202, chapter 3; 394; 684; 887; 1078; 1101; 1108; 1185; 1357; 1658; 1659; 1741; 1754; 1787; 1831; 1836, pages 22 - 24; 1838, page 57; 2484] scientific consensus [31, table 1 (particularly: 28; 574; 2534; 2535; 2536, updated in 32, figure 2 v007 on page 11, and 33, page 49 {with 2485 - 2495}); 499, page 28 in chapter 2; 500] that humans caused most of the post-1950s and post-1970s net global warming, primarily through humanity's release of CO2. This point extends to the industrial-era [35, page 2349; 72; 487; 492; 493; 494, page 1; 762; 1831; 2166] global warming of the late 19th, 20th, and early 21st centuries [35; 37; 45; 57; 60; 61; 63 - 65; 68; 69; 72; 74; 394; 887; 1078, figure 1A; 1150, figure 8.18 on page 699; 1357; 1659, with 1688; 1754; 1831], as per figures 22, 23, and 25. For instance, the Intergovernmental Panel of Climate Change (IPCC) notes that there is a 95% or greater [119, page 3] chance that most of the global warming from 1951 to 2010 was caused by humans [121, page 4; 373, page 869 and 884]. The IPCC also notes that there is 90% or greater chance [119, page 3] that man-made increases in greenhouses gases caused most of the warming from 1951 to 2010 [373, pages 869 and 884], with CO2 being the primary greenhouse gas released by human activity [121, figure SPM.2 on page 5]..

So let's see how Bradford Hill considerations support this evidence-based consensus on CO2-induced warming, starting with the metric of "plausibility."

Section 2.2: Plausibility / a well-evidenced causal mechanism

Astrology claims that distant planets, etc. strongly influence people's lives and personalities [122 - 124]. Astrology remains deeply implausible since astrologists provide no evidence-based mechanism via which astronomical bodies could strongly affect people lives and personalities [122, section 4.3; 124, pages 1571 and 1572]. Some critics accuse the myth proponent Nicola Scafetta of resorting to something like astrology [125 - 128; 937; 1225; 1381]. Scafetta [129 - 131; 1223; 1224; 1369; 1382], among others [937; 1193; 1270, from 14:37 to 18:52; 1650 - 1652], looks for correlations between Earth's climate and astronomical phenomena, such as Jupiter's and Saturn's tidal forces [129 - 131; 1223; 1224; 1382]. And as with astrologers, Scafetta (and others [1371; 1498 - 1500]) use a "phenomenological" approach to side-step the need to provide a detailed, evidence-based mechanism for how these astronomical factors strongly influence phenomena on Earth [132, section 6 on pages 12 - 14]. His pseudo-astrological account predicts slight global cooling after about 2001 [131, figure 12; 1223, figure 16; 1224, figure 6; 1382, page 74 and figure 5 on page 82; 2137], though post-2001 warming actually occurred, as I discuss in section 2.5, "Myth: No Global Warming for Two Decades", and section 2.1 of "Myth: The IPCC's 2007 ~0.2°C/decade Model-based Projection Failed and Judith Curry's Forecast was More Reliable".

Other non-astrological astronomical explanations of climate change hinge on spurious correlations that quickly break down [ex: 2200, with 2315; 2201; 2202; 2205; 2206], or are based on easily-debunked, physically implausible mechanisms [ex: 2202 - 2204]. And sometimes contrarians drop the "pseudo-" in "pseudo-astrology," by using astrology to explain climate change, as in the case of the astrologist Theodor Landscheidt [1565]. As with Scafetta [131, figure 12; 1223, figure 16; 1224, figure 6; 1382, page 74 and figure 5 on page 82; 2137], Landscheidt forecasted cooling [1566] when warming instead occurred. Amazingly, quite a number of contrarians treat Landscheidt's claims as being credible [1566 - 1573].

Fortunately, mainstream climate science is not astrology. Unlike astrologers, mainstream climate scientists offer well-evidenced mechanisms to account for cause-and-effect relationships. For instance, since at least the 1800s, scientists have known how greenhouse gases cause warming [133, page 1328; 134; 135, page 68; 137, from 5:40 to 7:46, and 9:12 to 14:08; 1171, pages 10 - 14; 1182, section on "The carbon dioxide greenhouse effect"; 1512, page 117; 1578, from 11:27 to 15:20; 1839; 1999]; a warming effect was known since at least Eunice Foote's 1856 work [1386, page 383; 1387; 1817]. Unfortunately, many members of the public do not understand the mechanisms underlying greenhouse-gas-induced warming, as discussed below (though education can remedy this lack of knowledge [136; 155; 156], increasing public acceptance of climate science [136; 835; 836; 1558, using 1559] and concern about climate change [836 - 839]):

Other non-astrological astronomical explanations of climate change hinge on spurious correlations that quickly break down [ex: 2200, with 2315; 2201; 2202; 2205; 2206], or are based on easily-debunked, physically implausible mechanisms [ex: 2202 - 2204]. And sometimes contrarians drop the "pseudo-" in "pseudo-astrology," by using astrology to explain climate change, as in the case of the astrologist Theodor Landscheidt [1565]. As with Scafetta [131, figure 12; 1223, figure 16; 1224, figure 6; 1382, page 74 and figure 5 on page 82; 2137], Landscheidt forecasted cooling [1566] when warming instead occurred. Amazingly, quite a number of contrarians treat Landscheidt's claims as being credible [1566 - 1573].

Fortunately, mainstream climate science is not astrology. Unlike astrologers, mainstream climate scientists offer well-evidenced mechanisms to account for cause-and-effect relationships. For instance, since at least the 1800s, scientists have known how greenhouse gases cause warming [133, page 1328; 134; 135, page 68; 137, from 5:40 to 7:46, and 9:12 to 14:08; 1171, pages 10 - 14; 1182, section on "The carbon dioxide greenhouse effect"; 1512, page 117; 1578, from 11:27 to 15:20; 1839; 1999]; a warming effect was known since at least Eunice Foote's 1856 work [1386, page 383; 1387; 1817]. Unfortunately, many members of the public do not understand the mechanisms underlying greenhouse-gas-induced warming, as discussed below (though education can remedy this lack of knowledge [136; 155; 156], increasing public acceptance of climate science [136; 835; 836; 1558, using 1559] and concern about climate change [836 - 839]):

"However, the public virtually never sees cogent scientific explanations of global warming's mechanism.

[...]

Yet we might expect scientifically literate people to produce a brief, mechanistic, global warming explanation—as in these 35 words: “Earth transforms sunlight's visible light energy into infrared light energy, which leaves Earth slowly because it is absorbed by greenhouse gases. When people produce greenhouse gases, energy leaves Earth even more slowly—raising Earth's temperature [emphasis added] [136, pages 51 - 52].”"

To elaborate on this further, let's start with an analogy. Imagine an open pot of water, placed over a fire. The pot takes in energy from the fire, and also releases energy into the environment. One can add fuel to the fire, strengthening the fire and thus adding more energy to the pot, generating an energy imbalance in which the pot takes in more energy that the pot releases. The pot warms in response, releasing more energy as it warms; the more sensitive the pot is to the energy imbalance, the more the pot warms. The pot will stop warming in response to the pot releasing as much (or more) energy than the pot takes in, yielding an energy balance and an equilibrium in which the pot takes in about as much energy as it releases.

Earth's climate operates on the same general principle of temperature changes in response to an energy imbalance. Earth's surface takes in shorter-wavelength (higher energy) solar radiation and releases longer-wavelength (lower energy) radiation. If Earth releases less energy than it takes in, then this creates an energy imbalance, which results in Earth warming [37; 142 - 144; 148; 688; 918, chapter 4; 1221]. Greenhouse gases such as CO2 and methane, emit radiation and transfer energy via colliding with other molecules. CO2 also absorbs some of the longer-wavelength radiation emitted by the Earth, but not incoming shorter-wavelength solar radiation, with CO2 absorbing radiation in specific wavelengths [137, from 9:13 to 10:28; 138 - 141; 145 - 147; 149; 151; 315; 317; 688; 918, chapter 4; 1074; 1269; 1426].

Thus greenhouse gases such as CO2 engage in radiative forcing [37; 138; 139; 144; 145; 149; 317; 688; 1074; 1150, section 8.1; 1269; 1399; 1578, from 3:18 to 4:45; 1737; 1927; 2132], slow the rate at which Earth releases energy, and cause an energy imbalance [37; 142 - 144; 148; 151; 688; 918, chapter 4; 1221; 1269; 1737; 1924] that results in warming. Radiative forcing, with its units of watts per square meter (energy per unit of space per unit of time) [37; 138; 139; 144; 145; 149; 317; 688; 1074; 1150, section 8.1; 1269; 1399; 1578, from 3:18 to 4:45; 1737], measures that energy imbalance. There are other technical aspects of this process, such as an increasing effective radiation altitude in response to the mechanism described above [149, figures 1 and 3; 180, pages 446 - 447; 434, page 25; 696, figure 3.6 on page 119 and page 122; 1421, from 2:54 to 5:49; 1556, from 11:20 to 24:41; 1853, section 3; 2364; 2365; 2372, from 11:23 to 14:16; 2563; 2564, page 10; 2566, page 962; 2571, page 1035], but the aforementioned points should suffice for this blogpost. CO2-induced warming also melts solar-radiation-reflecting ice, increases water vapor levels, and affects cloud cover; this increases the amount of shorter-wavelength solar radiation absorbed by the Earth [179; 1122 (with 2548, 2569, and 2570); 1420; 2566, figure 4 and page 962], as I discuss later in this section.

Earth's climate operates on the same general principle of temperature changes in response to an energy imbalance. Earth's surface takes in shorter-wavelength (higher energy) solar radiation and releases longer-wavelength (lower energy) radiation. If Earth releases less energy than it takes in, then this creates an energy imbalance, which results in Earth warming [37; 142 - 144; 148; 688; 918, chapter 4; 1221]. Greenhouse gases such as CO2 and methane, emit radiation and transfer energy via colliding with other molecules. CO2 also absorbs some of the longer-wavelength radiation emitted by the Earth, but not incoming shorter-wavelength solar radiation, with CO2 absorbing radiation in specific wavelengths [137, from 9:13 to 10:28; 138 - 141; 145 - 147; 149; 151; 315; 317; 688; 918, chapter 4; 1074; 1269; 1426].

Thus greenhouse gases such as CO2 engage in radiative forcing [37; 138; 139; 144; 145; 149; 317; 688; 1074; 1150, section 8.1; 1269; 1399; 1578, from 3:18 to 4:45; 1737; 1927; 2132], slow the rate at which Earth releases energy, and cause an energy imbalance [37; 142 - 144; 148; 151; 688; 918, chapter 4; 1221; 1269; 1737; 1924] that results in warming. Radiative forcing, with its units of watts per square meter (energy per unit of space per unit of time) [37; 138; 139; 144; 145; 149; 317; 688; 1074; 1150, section 8.1; 1269; 1399; 1578, from 3:18 to 4:45; 1737], measures that energy imbalance. There are other technical aspects of this process, such as an increasing effective radiation altitude in response to the mechanism described above [149, figures 1 and 3; 180, pages 446 - 447; 434, page 25; 696, figure 3.6 on page 119 and page 122; 1421, from 2:54 to 5:49; 1556, from 11:20 to 24:41; 1853, section 3; 2364; 2365; 2372, from 11:23 to 14:16; 2563; 2564, page 10; 2566, page 962; 2571, page 1035], but the aforementioned points should suffice for this blogpost. CO2-induced warming also melts solar-radiation-reflecting ice, increases water vapor levels, and affects cloud cover; this increases the amount of shorter-wavelength solar radiation absorbed by the Earth [179; 1122 (with 2548, 2569, and 2570); 1420; 2566, figure 4 and page 962], as I discuss later in this section.

The IPCC depicts this process as follows:

This process is somewhat analogous to what happens to you when you wear a thick blanket [151, page 38; 154; 433, pages 38 - 39; 434, page 25; 435; 1737; 2349]. Your body generates heat through muscle contractions and other processes, somewhat analogous to the Sun adding shorter-wavelength radiation to Earth. Your thick blanket traps air near your skin, slowing the rate at which you release heat energy into the environment through your skin, somewhat akin to how increased greenhouse gas cause warming via an energy imbalance. Thus the blanket creates an energy imbalance, causing you to warm [154; 430 - 432; 433, page 38; 1737]. This blanket-induced warming can damage the body in certain cases, especially in young children [431; 432]. In addition to this blanket analogy, other sources provide different comparisons that help illustrate the aforementioned greenhouse gas effect at a layman's level [136; 149 - 156; 688; 696, page 122; 1074; 1418; 1419; 1421; 1512, page 117; 1517; 1556, from 8:25 to 23:23; 1604; 1737; 1797; 1815; 1819; 1853; 1874; 1959; 1974; 2010, section 2.1.2; 2139; 2140; 2372; 2566, pages 957 - 958]. Infrared-reflective coatings offer another analogy. Since at least the 1920s, scientists and engineers knew that one could coat glass with a film that allows shorter wavelength radiation (visible light) to pass through, while reflecting longer wavelength (infrared) radiation back. This reflected energy helps increase energy efficiency [2235 - 2241]. Other products, such as CO2 lasers, more directly exploit the absorption and infrared emission properties of CO2 [2242 - 2245].

Some individuals on the Internet make nonsensical criticisms of the science on the greenhouse gas effect [150; 153; 154; 157 - 166; 366; 730; 732; 733; 939; 1103; 1110; 1815]; this applies especially to critics who attempt to replace the greenhouse effect with atmospheric pressure [154; 158; 160; 162; 165; 166; 366; 939; 1089; 1366; 1376; 1377; 1436 - 1438; 1481; 1576; 1638; 1756; 1814]. Many of these critics, or sky dragon slayers [157; 730; 733; 734], claim that the greenhouse effect violates the second law of thermodynamics. The slayers argue that the net flow of energy should be from the hotter object to the colder object, as per the second law. Yet the greenhouse effect (supposedly) assumes that a greenhouse-gas-rich atmosphere warms the surface, even though the lower atmosphere is colder than the surface [150; 153; 157 - 159; 732; 733; 1165; 1166; 1365; 1593, from 16:10 to 21:37; 1815].

But the slayers' criticism makes no sense, as illustrated by the blanket analogy. The blanket can warm you via an energy imbalance, even if the blanket is cooler than your body temperature; so a heated blanket is not required for warming you. Analogously, greenhouses gases do not need to make Earth's atmosphere warmer than the rest of the Earth, in order for these gases to warm Earth.

Or to give another analogy: suppose a pump above a pool of water adds water to the pool. A drain at the bottom of the pool allows water to flow out and into a tank downhill of the pool. There are at least two ways to increase the water level in the pool: increase the amount of water pumped in from above, or constrict the drain to limit the amount of water that leaves from below. The latter method works even though, with respect to the drain, the net flow of water is still downhill into the tank rather than uphill into the pool. Figure 3 below summarizes how constricting the drain would increase the level of water in the pool:

Analogously, there are at least two ways to warm the Earth. One can increase the amount of shorter-wavelength radiation coming in, such as by increasing solar radiation [811 - 815]. Or one can slow Earth's release of longer-wavelength radiation, such as by increasing greenhouse gas levels [37; 142 - 144; 148; 151; 688; 918, chapter 4]. This latter method still works even though, with respect to the atmosphere, the net flow of longer-wavelength radiation is still out from the surface to the atmosphere and then into space [150; 151, page 38; 316, figure 1; elaborated explanation from me: 2054].

This runs contrary to the slayers' faulty criticism, which claims that the greenhouse effect involves the net flow of longer-wavelength radiation in from the greenhouse-gas-rich atmosphere to the surface. Or to put in terms of the pool analogy: the slayers' nonsensical criticism is akin to saying that constricting the drain increases the pool's water level only if the net flow of water is uphill from the tank into the pool. Thus the slayers' critique fails since it depends on a misrepresentation of the greenhouse effect.

The contrarians' objection states that the machines create new water, since the machines release +10 downwards, which is more than the +5 the pool adds to the tank. This objection fails since it focuses on the gross exchange of water, not the net exchange. For the machines to create new water for release, the machines must be net releasers; they must release more water than they take in. But the machines are not net releasers since they take in as much water as they release, re-directing some of the water surface-ward. So the contrarian objection lacks merit. Similarly, greenhouse gases do not create energy, but instead absorb and re-direct it. So when ones takes into account the net flow of energy (the sum of incoming solar radiation, upward infrared radiation, downward infrared radiation, etc.), the greenhouse gas effect does not violate the first law of thermodynamics. The effect's downward infrared radiation remains consistent with conservation of energy [150; 316, figure 1; elaborated explanation from me: 2054].

But the slayers' criticism makes no sense, as illustrated by the blanket analogy. The blanket can warm you via an energy imbalance, even if the blanket is cooler than your body temperature; so a heated blanket is not required for warming you. Analogously, greenhouses gases do not need to make Earth's atmosphere warmer than the rest of the Earth, in order for these gases to warm Earth.

Or to give another analogy: suppose a pump above a pool of water adds water to the pool. A drain at the bottom of the pool allows water to flow out and into a tank downhill of the pool. There are at least two ways to increase the water level in the pool: increase the amount of water pumped in from above, or constrict the drain to limit the amount of water that leaves from below. The latter method works even though, with respect to the drain, the net flow of water is still downhill into the tank rather than uphill into the pool. Figure 3 below summarizes how constricting the drain would increase the level of water in the pool:

Analogously, there are at least two ways to warm the Earth. One can increase the amount of shorter-wavelength radiation coming in, such as by increasing solar radiation [811 - 815]. Or one can slow Earth's release of longer-wavelength radiation, such as by increasing greenhouse gas levels [37; 142 - 144; 148; 151; 688; 918, chapter 4]. This latter method still works even though, with respect to the atmosphere, the net flow of longer-wavelength radiation is still out from the surface to the atmosphere and then into space [150; 151, page 38; 316, figure 1; elaborated explanation from me: 2054].

This runs contrary to the slayers' faulty criticism, which claims that the greenhouse effect involves the net flow of longer-wavelength radiation in from the greenhouse-gas-rich atmosphere to the surface. Or to put in terms of the pool analogy: the slayers' nonsensical criticism is akin to saying that constricting the drain increases the pool's water level only if the net flow of water is uphill from the tank into the pool. Thus the slayers' critique fails since it depends on a misrepresentation of the greenhouse effect.

Other contrarians distort conservation of energy / the first law of thermodynamics, instead of the second law. The first law states that energy is neither created nor destroyed, but instead only shifts forms. The contrarians claim the greenhouse gas effect violates this law by creating energy that was not inputted by the Sun or some other source [150; 2348; 2349; 2350, page 10; 2351 - 2353; 2371]. This objection lacks merit because it conflates gross with net. The previous pool analogy, when adapted to figure 2, illustrates this point.

Imagine machines lie in the pool, half-way between the pool's top surface and the pool's drain-adjacent bottom. The machines take in some water heading towards the drain. The machines then shoot out this water randomly in all directions. Thus the machines take water that was heading drain-ward, and send it some of it surface-ward. This re-direction reduces drain-ward flow of water. Adding a sufficient number of machines slows the flow of water through the drain to the point that the drain releases less water than the pump adds, thereby increasing the level of water in the pool. The action of the machines parallels (with inverted directions) the right half of figure 2, in which greenhouse gases absorb infrared radiation heading upwards from Earth's surface and then send some of that energy downwards towards Earth's surface.

Now suppose a water balance exists in the pool, such that the pool maintains a constant volume of water. The rate of exchange of water is as follows, in liters per minute (positive numbers indicate water entering the pool, and negative numbers indicate water exiting the pool):

Imagine machines lie in the pool, half-way between the pool's top surface and the pool's drain-adjacent bottom. The machines take in some water heading towards the drain. The machines then shoot out this water randomly in all directions. Thus the machines take water that was heading drain-ward, and send it some of it surface-ward. This re-direction reduces drain-ward flow of water. Adding a sufficient number of machines slows the flow of water through the drain to the point that the drain releases less water than the pump adds, thereby increasing the level of water in the pool. The action of the machines parallels (with inverted directions) the right half of figure 2, in which greenhouse gases absorb infrared radiation heading upwards from Earth's surface and then send some of that energy downwards towards Earth's surface.

Now suppose a water balance exists in the pool, such that the pool maintains a constant volume of water. The rate of exchange of water is as follows, in liters per minute (positive numbers indicate water entering the pool, and negative numbers indicate water exiting the pool):

- rate pump adds water to the pool : +5

- rate water exits the pool through the drain into the tank : -5

- rate machines take in water from the pool : -20

- rate machines release water into the pool (sum of all directions) : +20

- rate machines release water into the pool (only surface-ward direction) : roughly +10

Radiation-induced [138; 141; 145; 149; 208; 1530; 2024; 2025, with 2274 and 2275; 2065; 2273; 2276 - 2278; 2402; 2584] warming from greenhouse gas increases occurred [208; 1530; 2273; 2275, with 1924; 2277; 2278; 2402; 2584], as discussed further in section 2.4. So given the aforementioned discussion, the greenhouse effect provides an evidence-based mechanism via which CO2 increases cause warming. Other non-CO2 factors also impact this CO2-induced warming. In response to warming, positive feedbacks amplify subsequent warming and negative feedbacks limit subsequent warming [167; 168; 437; 1263]; I discuss this further in section 2.8, along with "Myth: No Hot Spot Implies Less Global Warming and Support for Lukewarmerism". Evidence-based causal mechanisms underlie each one of these feedbacks. The primary long-term feedbacks are [169; 170, section 1; 171; 179; 1065; 1122; 1956; 2408] (see figure 4 for the relative magnitude of some of these feedbacks; other smaller feedbacks exist, such as positive feedback from methane causing more global warming, as warming lakes and warming-induced melting of ice releases more methane [1401 - 1405; 1654, page 14]):

- Water vapor as a positive feedback [179; 1122; 2408]: Warming evaporates liquid water to form water vapor. This increases water vapor levels in the air [172 - 176; 688], because warmer air can hold more water vapor [169; 170, section 1; 177; 178; 688; 1050; 1058]. More water vapor causes further warming, since water vapor is a greenhouse gas [169; 175; 179 - 182; 688; 1058; 1604; 2010, paragraph 25 and section 3.1] (see sections 2.3 and 2.8 for further discussion).

- Clouds as a positive feedback: Clouds reflect solar radiation into space, or emit infrared radiation into space, and thus can act as a negative feedback; clouds also reflect/absorb radiation emitted by the Earth or absorb solar radiation and thus can act as a positive feedback [177; 179; 183; 184; 1122]. Lower level clouds tend to act as a negative feedback, while higher level clouds tend to act as a positive feedback [170; 177; 183 - 185; 1577]. Climate models predict a net positive feedback from clouds, with radiative forcing from clouds becoming more positive with warming, due to increases in higher level clouds and reductions in lower level clouds in response to warming [183; 186; 213; 214]. For instance [1948], suppose in 1990 clouds have a net cooling effect of -2.0 K/year. Then it warmed for 10 years due to non-cloud factors, leading to clouds having a more positive cooling effect of -1.5 K/year by 2000, allowing for more warming for 10 years, leading to the clouds having an even more positive cooling effect of -1.0 K/year by 2010, allowing for more warming, and so on. This illustrates how positive feedback from clouds can augment warming, even if clouds overall have a cooling effect each year. So what matters for feedback is how the clouds' impact changes with temperature changes, not necessarily whether the sign of the clouds' impact is positive or negative at a given point in time. A similar point applies to other feedbacks.

- Surface albedo as a positive feedback: Ice has a greater albedo than liquid water, meaning that ice reflects more visible light from the Sun back into space than does liquid water. Melting ice therefore reduces Earth's albedo and increases the amount of radiation absorbed by Earth's surface [11; 170; 187; 688]. This increase in absorbed radiation causes more surface warming and therefore more ice melt; thus melting ice acts as a positive feedback amplifying warming [171; 188 - 191; 688; 1122].

- Lapse rate reduction as a negative feedback: Temperature in the troposphere, a lower layer of the atmosphere, decreases with increasing height; the rate of decrease is known as the tropospheric lapse rate. The magnitude of the lapse rate decreases when the upper troposphere warms faster than the lower troposphere, and when the lower troposphere warms faster than the surface, especially in the tropics. Transferring warming from the surface up to the troposphere thus reduces the lapse rate [137, from 31:01 to 31:48; 172; 173; 179; 192, pages 4 and 22; 193 - 196; 197, pages 7 and 8; 198, pages 101 and 102; 1798 - 1800; 1943] and allows Earth to more easily radiate this energy into space. So lapse rate reduction limits global warming [169 - 171; 173; 179; 196; 199 - 201; 202, section 2.6.1 on page 90; 203, figure 3c on page 5 and page 16; 204; 1263; 1798 - 1800; 1943; 2408]. In contrast to the tropics, within the Arctic the surface warms faster than the lower troposphere and the lower troposphere warms faster than the upper troposphere [137, from 29:38 to 31:01; 180, page 445; 197; 198; 551; 1226 - 1231; 1232, page 375; 1263; 1798; 1943], leading to a lapse rate increase and a positive lapse rate feedback in the Arctic [171; 437; 1226; 1233 - 1239; 1263; 1798; 1799; 1943].

- Planck feedback as a negative feedback: As Earth warms, Earth radiates more energy into space, as per the Stefan-Boltzmann law. This increased radiation represents the Planck feedback and serves as a negative feedback that limits the amount of energy Earth accumulates as Earth warms [151, page 33; 169; 170, section 1; 202, section 2.6.1 on pages 89 - 90; 436 - 438; 1213; 1420; 1578, from 4:44 to 6:29; 1956].

These feedback mechanisms are borne out in reality. Water vapor [170; 200; 205 - 212; 290; 292; 1054; 1058; 1261; 1787; 1788, page S28; 2024], clouds [170; 185; 186; 200; 213 - 219; 1338; 1379; 1518; 1520; 1577; 1787; 1871; 1955], and reduced surface albedo [188 - 190; 200; 220 - 222; 1787] acted as positive feedbacks amplifying global warming. And in the tropics, the mid-to-upper troposphere warmed more than near the surface, as shown in satellite analyses [193, figure 9B on page 385; 223, table 4 on page 2285; 224; 225], weather balloon analyses [226, figure 2c; 227, figure 9; 228, figures 1 and 2], re-analyses [229, figure 23 on page 348 and section 10.2.2 on page 351; 230, figure 7; 231, figure 1; 232, figure 4; 233, figure 4], and other sources [234; 235, as cited in 236, page 651]. This so-called tropospheric hot spot indicates that the tropical lapse rate decreased (I discuss this further in "Myth: The Tropospheric Hot Spot does not Exist"). This lapse rate reduction acted as a negative feedback limiting global warming [170; 173; 200; 203, figure 3c on page 5 and page 16; 204; 1787]. The Arctic near-surface also warmed faster than the Arctic upper troposphere [137, from 29:38 to 31:01; 188; 1109; 1240; 1241 - 1246, using 741, as per 742], indicative of a positive lapse rate feedback [171; 437; 1226; 1233 - 1239; 1263]. The processes underlying this positive lapse rate feedback contribute [1226; 1233; 1234; 1239; 1263; 1787] to strong surface warming in the Arctic [188; 759; 1013; 1240; 1247 - 1253, using 741, as per 742; 1787], resulting in greater surface warming in the Arctic than in the tropics and than the global average [137, from 29:38 to 31:01, and 31:47 to 33:34; 227; 228; 759; 1013; 1247 - 1253, using 741, as per 742; 1254 - 1256; 1787], consistent with climate models and basic physical theory [137, from 29:38 to 31:01, and 31:47 to 33:34; 197; 198; 437 551; 1227; 1229; 1231; 1232, page 375; 1263].

And in accordance with the Planck feedback, Earth released more radiation during the warm El Niño phase of an ocean cycle known as the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) [439 - 441]; the radiation increase occurred largely because El Niño increased cloud cover and these clouds then reflected the solar radiation Earth would otherwise absorb [439; 442]. This cloud-based mechanism compensated [223; 225] for less emission of radiation by clouds during El Niño [227; 228]. Thus Earth radiated more energy into space as Earth warmed [178; 443; 444].

In contrast to the temporary ocean warming events such as El Niño [445; 446], CO2 remains for much longer [5; 11 - 21; 447], driving a longer-term energy imbalance [37; 142 - 144; 1221]. Thus CO2 can cause long-term global warming, as CO2 has done in the past [11; 15; 182; 447; 1055] (ex: see the cited paleoclimate papers in figure 7), while El Niño does not, as I discuss in "Myth: El Niño Caused Post-1997 Global Warming". Eventually, however, CO2-induced warming stops, in part because increased radiation release by a warming Earth leads to an equilibrium in which Earth's release of energy into space equals the solar energy entering Earth [167; 349]. Figure 4 depicts a model-based estimate of how much various feedbacks contribute to warming upon equilibrium:

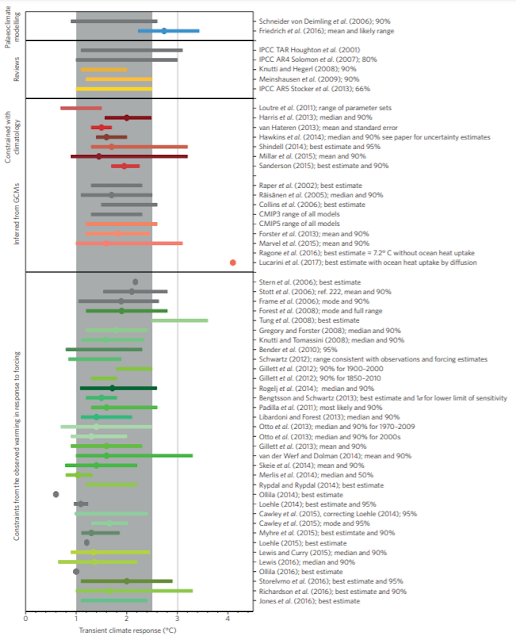

Figure 4: (a) Average temperature increase for a doubling of atmospheric CO2 levels, upon reaching equilibrium, in atmosphere-ocean general circulation models (GCMs) from CMIP3 (phase 3 of the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project). This temperature increase is also known as equilibrium climate sensitivity, or ECS; I discuss ECS further in section 2.5. Panel a also depicts the contribution of various feedbacks to this temperature change in the CMIP3 models. The Planck response represents temperature response to forcing from CO2, without taking other feedbacks into account [68; 533, section 2.6.1 on page 90 - 91]. (b) Average relative magnitude of each feedback in the CMIP3 models, with stronger positive feedbacks having a more positive value and stronger negative feedbacks having a more negative value. Error bars indicate +/- one standard deviation [169, figure 5; also see 1065, figure 1].

|